When we want to ensure two actors make a decision before seeing the decision of the other actor. Done through commits, where one actor sends a commitment which stores the encrypted decision to the other actor. Then the second actor sends back their decision. Finally, the first actor sends the key for decrypting the commitment to see the decision.

security:

security: indistinguishable from truly random.

security: indistinguishable from truly random function (black-box).

PRF is (q, t, \varepsilon)-secure if for all bounded \mathcal A Adv(\mathcal A) = P[b' = 1 | b = 1] - P[b' = 1 | b = 0] is negligible. Where q is the amount of queries done with complexity t.

security: one-way

There is no key that allows to reverse a hash.

| algorithm | digest | comment |

|---|---|---|

| MD5 | 128 | broken |

| SHA-1 | 160 | broken |

| SHA-2 | 224, 265, 384, 512 | |

| SHA-3 | 224, 265, 384, 512 |

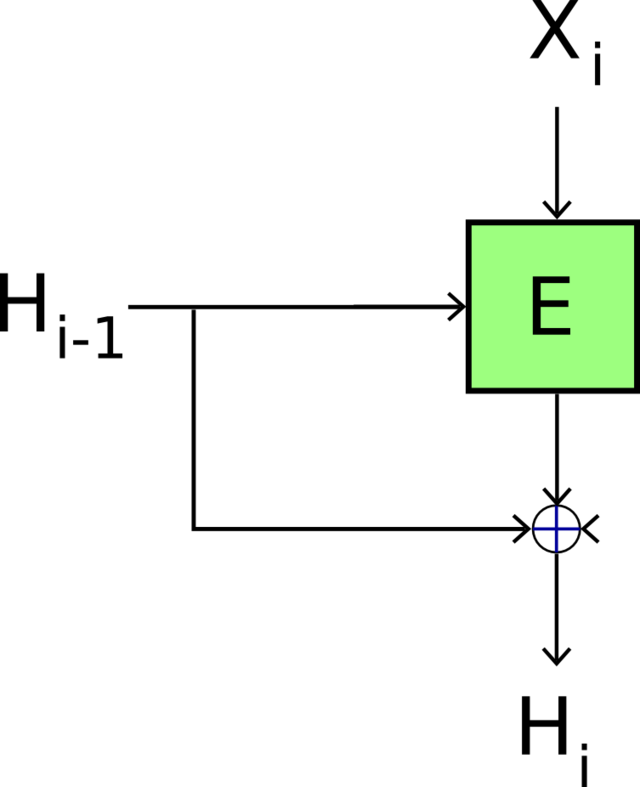

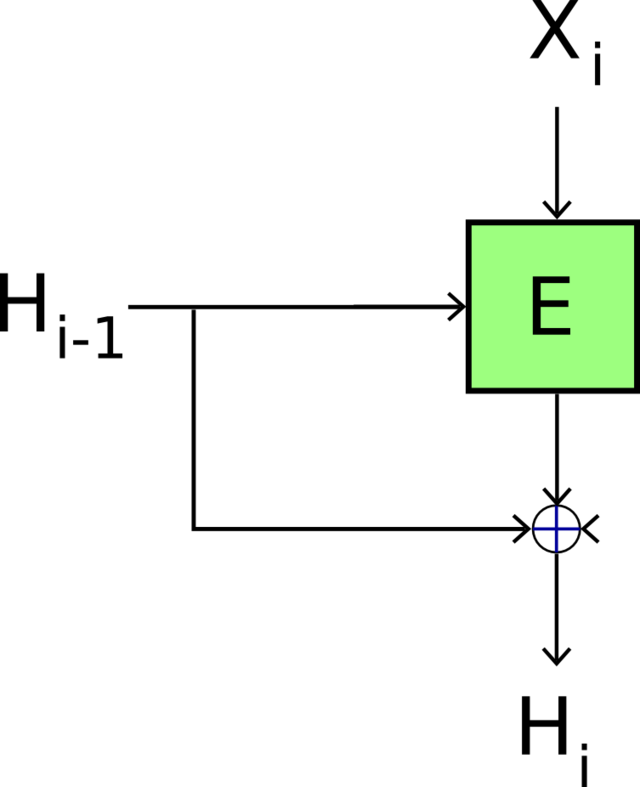

Treat the message as keys into some encryption function. Encrypt blocks with some seed value. Xor results of individual blocks. Pad the message if needed.

If the encryption function is collision resistant then the resulting hash function is collision resistant.

For padding messages. pad = |1|0\cdots 0 |\textit{length}| where length is a 64-bit number.

Authentication and verification of messages.

security: unforgeability

Given a hash function H create a MAC. First key is padded (or truncated) with zeros to the fixed length. Then:

\text{HMAC}_K(X) = H((K \oplus \text{opad}) || H((K \oplus \text{ipad})||X))

Where opad is repeated 0x5c and ipad is repeated

0x36.

If compression function is PRF then HMAC is PRF.

CBC mode of operation. MAC is the result of the last block of encryption. We use and IV equal to 0.

It is not secure as an attacker can engineer same MAC by appending something to the message. It is secure if the message length is fixed.

CBCMAC but we additionally encrypt the final output.

CBCMAC but last block is XORed with k_{case} before encryption. Output is truncated.

It exists.

Let (h_K)_{K \in_U \mathcal K} be a family of hash functions from D to \{0, 1\}^m defined by a random key K which is chosen uniformly from a key space \mathcal K. This family is \varepsilon-XOR-universal if for any a and x \ne y in D,

P[h_K(x) \oplus h_K(y) = 1] \le \varepsilon

MAC_{K, K_i}(i, x) = h_K(x) \oplus K_i for a \varepsilon-XOR-universal hash function and unique K_i (cannot be reused).

| mode | comment |

|---|---|

| CCM | CTR + CBCMAC |

| GCM | CTR + WC-MAC |

| GCM-SIV | CTR + WC-MAC |

| ChaCha20-Poly1305 | stream cipher + WC-MAC |

Takes plaintext plus extra data.

Game:

Game:

Oracle OMac(X):

Game:

Oracle OMac(X):

secure against forgeries \implies secure against key recovery

Adv = Pr[\Gamma_1 \text{ returns } 1] - Pr[\Gamma_0 \text{ returns } 1]

Game \Gamma_b:

O(X):

secure against distinguisher \implies secure against forgeries

The probability of picking the same number twice from \{1, \cdots, N\} when picking n times with uniform probability is p = 1 - \frac{N!}{N^n(N - n)!}

For \theta = \frac{n}{\sqrt{N}}, p \stackrel{N \to \infty}{\longrightarrow} 1 - e^{-\frac{\theta^2}{2}}

If we start with x that is outside of a cycle and then continuously hash x, h(x), h(h(x)), etc, we eventually reach enter a cycle. Let h_t(x) be the point where we enter the cycle. If we continue hashing, eventually h^k(x) = h_t(x) where k \ne l (because we are in a cycle and we entered to it from a different side). This means h^{k-1}(x) and h_{t-1}(x) are two different values that hash to the same thing: a collision.